The Intimacy of Elizabeth Cotten

What it means for a song about death to be written by a child and sung by an elder.

A Living Paradox

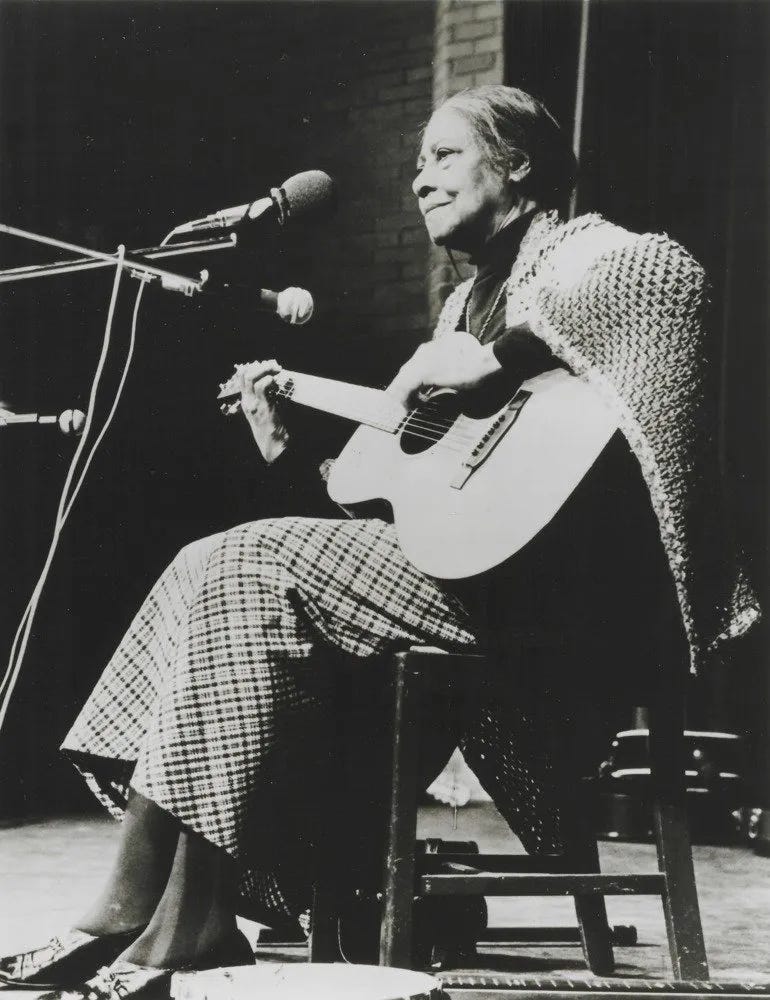

In the morning, just a few weeks ago, I found myself glued to the whiteboard. It was a vintage clip of Elizabeth Cotten, born in 1892, playing a song she wrote when she was only 11 years old.

The teacher in the classroom pointed out something remarkable: Cotten’s guitar was upside-down and backwards. We watched as she plucked the melody with her thumb and the bassline with her index finger. The other three fingers rested delicately on the face of her instrument. Her ease was mesmerizing.

“That’s impossible,” my dad said when I explained her unique “Cotten picking” style. But once he saw the clip and realized her guitar was upside-down and backwards, he smiled and said, “The self-taught ones are the best.”

Elizabeth Cotten’s understated playing was like that of a highly original crocheter, producing a crystal clear tapestry in sound.

What impressed me most wasn’t just her technique. It was the harmonies that rose that convinced me I was in the presence of a genius.

After the class, I drove home thinking about it. Passing by the lights and signs along the road, I tried to piece together how those eight bars worked.

One thing was certain: the chords felt smooth. The first four bars are a familiar pattern: I-V-V-I. That much was clear. (For simplicity, I kept things in C major.) I could hear from the beginning that the G was sustained over the first four bars as a pedal, keeping things steady. Massive, even [figure 2].

The fifth bar is where things take a turn. It’s what hooked my classical ear. You can hear the signature sound of the blues come through in bar five. A new color, a new direction. It’s what makes your right shoulder lean in a bit, into sweetness. There, you can hear that special blue tone bringing a sense of adventure and play.

I found myself doing a kind of harmonic calculus to figure out that measure. Was it a kind of double dominant? The blue tone resolves up to an unexpected place in bar six, somewhere closer to the home key. Maybe this blue harmony is a rare major III chord? I tried singing it. Ah yes, it could be.

I flipped on my left turn signal when it felt like I had identified it: the G rises to a G# in bar five.

When I made it home, I grabbed my pen and wrote the song down. I had to see how this eight-bar harmonic story aligns with the pitches.

It’s funny — I shared a clip of the digital transcription, without context, with a friend who initially thought I had composed it. She praised it like she praised none of my other pieces, and insisted that I commercialize music like this, to which I replied, “Oh, you think I wrote this? This was written by Elizabeth Cotten when she was a kid, most likely in her sleep.” It all made sense later when I sent her the original.

I would come to learn that Cotten did first hear this music at night. The sound of a locomotive near her home in North Carolina used to keep her up late, which is, in her words, what must have given her “the mind to write about the freight train.”

Two mornings in a row, I would wake with extra sunshine in my room and her song in my chest. I realized one afternoon that I had grown to love it the same way I once loved Beethoven’s Violin Concerto when I was eleven. I used to come home from school and pop my dad’s CD into the stereo (Heifetz with the Boston Symphony). I’d turn the volume up as loud as I could, and let it flood the house and envelop me in a story I could feel, characters and plot and all. It was my timeless escape. The piece energizes my soul to this day. But now, things feel a lot more simple inside. Now, the sunshine pours in, not to a blazing canonical work, but to a small, popular hit from a Black American woman living in 1907.

Heifetz, and his cold-hard virtuosity, showed me what an individual could achieve through isolation and discipline (and scales, arpeggios and fear). Cotten offers something else. Something shared. Through her voice, I can hear the glow of the common, everyday person. It made me remember what Celibidache once said: symphonic music is not about virtuosity.

Perhaps the deepest music never is.

Freight train, freight train, runs so fast Freight train, freight train, runs so fast Please don’t tell what train I’m on They won’t know what route I’m gone. When I am dead and in my grave, No more good time here I crave Place the stones at my head and feet Tell them all that I’ve gone to sleep. When I die, Lord, bury me deep Way down on ol’ Chestnut street Then I can hear ol’ number nine As she come rollin’ by.

The harmonies, while adventurous, are all simple major chords. But these lyrics? PHEW.

This is a prayer. This is a contemplation of mortality. This is a deep longing for eternal peace.

When I first started singing the lyrics myself, they felt odd to say. Odd in the same way The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying felt when I first read it. Tibetan Buddhism is a culture that centers the experience of death, something many Westerners are taught to fear. Until you confront it (and realize it might not be so bad as long as you’ve lived well) that oddness stays with you. Singing Cotten’s lyrics in a major key only increases that feeling. But that’s the genius: singing of death in a major mode.

With lyrics on top, the harmonies carry a quiet acceptance. This is hardship, un-shamed, released through the resonant power of the major chord.

I thought about that first stanza, the plead, while driving someplace else. I nearly teared up. How is it that such a poem could do that? Is it because I know the history? Because I know how sweet and simple the song goes? Perhaps both. Perhaps I’m moved by the beauty of an 11 year old invoking trains as a symbol of passing between life and death.

Wondering about the power of words made me remember something Benjamin McEvoy said. Benjamin is the creator of Hardcore Literature, and he has an amazing theory of poetry: the words of a poem unlock something within us chemically, tracing deep and ancient neural pathways, producing reality-altering effects.

However it works, when she sings it to you, you feel both what is said and what is unsaid. No more good times here I crave. It makes you ask, what kind of life did she have at 11 to be singing this? To speak so deeply to the soul’s longing to run from hard times, to disappear, to be gone. I couldn’t be more grateful to her for enshrining her experience in song.

And then, the image of Cotten at 92 singing the song she wrote at 11 seems to tell the paradoxical story of life itself. Something is here, transforms in miraculous ways, and ultimately leads to rest for good. By singing this well into her old age, Cotten became an emblem of lightness and perseverance.

She sounds so sad when she says the train runs so fast. It’s as if, through all her experiences, she realizes just how true her younger self was. And each time, she honors her truth by singing it with reverence.

I think she was wise to honor the observations of children.

Every now and then, my nephew says things that make me pause. He recently said to me, “You’re a grown-up boy.” I responded, “Yes, I’m a man,” thinking I was teaching him something new. He insisted, slower, with his higher pitched voice: “No, you are a grown-up boy.” And it’s like, oh, well yes, he’s right. I see what he’s saying now. It’s a nice observation. It was one of those childlike truths that reframe what the rest of us thought we knew.

When I see Elizabeth Cotten singing Freight Train at 92, I see what Miyazaki reveals in Howl’s Moving Castle: that the spirit of a young girl still lives inside every old woman’s body. Shocking, but true. Yes. It is timeless.

When I hear Elizabeth’s voice now, I hear time folding on itself. I hear the sound of a girl and a woman sharing one breath.

The Harmonies

Figure 1. Freight Train, 8 bars, named. I-V-V-I-III7-IV-V-I.

The transcription. The ‘Cotten picking’ style plays the Melody staff with the thumb a the Bass staff with the index finger of the right hand. It is amazing to see one guitarist could play both lines with only two fingers.

Figure 2. Smooth chord connections. The passage between C major and G major is made smooth because Cotten keeps the common tone between the two chords, G, in the bass.

Figure 3. A smooth connection between mediant harmonies, CM and EM. The song features a change from C major to E major, to harmonize that blue note, G#. Despite being far away on the circle of fifths, C and E can be made to sound smooth together because they too share a common tone, E, which is also held over in the melody. The other two chord tones move in the smallest possible step contrary to each other; the tonic moves down and the fifth rises up, each by a half step.

Figure 4. The harmonic context. On the left, we can visualize E major’s distance from C major on the circle of fifths. E major is four fifths up from C major. On the right, we see E major’s hidden proximity to C major via its function as the dominant of A minor. The red numbers are the simplified order of chords in the progression. Even though E major is far away on the circle, the ear hears it as near to C within this song because E is the dominant of A minor, the relative minor of C major. (In the song, we do not hear A minor as expected after its dominant but instead slip to the lower fifth, F major, in bar six, a change that creates the mixed sense of adventure and being home at once.) The diagram on the right is a way to see how we stay very near to C major throughout the whole song.

Links

Elizabeth Cotten - Rare Live Performance (Youtube)

Thanks to Dina Rivel for reading an early draft of this essay, and to Scott Anderson for introducing his class to this legendary musician.