A woman in the audience let out a quiet gasp when she, along with the rest of us, realized, ‘This is the end.’

In the old church, when the string orchestra was dying down and dying away, the charcoal rapidly turned grey, and we all saw it congeal, we all saw the music crystalize together before our eyes into that crowned knot of fire, and we knew that we were no longer in the middle of something epic, tense and yearning, continuing… It had the feeling of being chased, as Ben once put it, hunted by some corrupt power. A single sounding string in the cello had been held, tense, above, while the rest of the music mercilessly carried on in a different tonality. The tones of the melody scorched against that sound, held taut, up there, excruciating. The double basses pounded rhythms into our eyes and flesh, tearing violins with warm metal and wood. But no... We were no longer in the midst of that elegy for strings. We were at the very, very end. And we all realized that we were finished. That it was done.

The sound had faded away. But the music continued well into the rest, well into the long silence left behind, and the sound perished like a tremor and became a distant memory.

An uproarious applause.

💐

We all know that music is an entirely different world from this one. The symbols of ‘that’ world—the rhythms, tonalities, and melodies—are not visual or linguistic, they are aural. They don’t imitate anything physically real. In this ‘different’ musical world, the forms and ideas are made of sound, they are sounding, and they need time in order for it to mean something, for its meaning to become apparent to us. Said another way, the meaning of music is inextricable from our perceptions of time.

What is also intimately true is that music is not all mystery. We can see quite well that the symbolic musical world mirrors our own. It is not such a foreign thing to a child, for example, when she hears music. Quite the contrary; children are at home when they are in the musical world.

Here is where we hit the heart of the problem: music is freaky when you try to analyze it. It begins to unfurl the moment you try pinning it down in thought. It’s infuriating if you’re someone who wants to name things. What can you even call something that has the power to hold you close at night and shake your world apart in the concert hall and make you feel entertained and ceremonial and transcendent all at once? What better name is there than music? It baffles the thinker not because it lacks logic, but because it carries deep contradictions inside its core. As Iain McGilchrist phrased it1, music is at once of this world and yet far beyond it. It is at once universal and particular. It unfolds in time yet lifts us outside of time. Music is nothing but a lived reality.

In music and in ‘this’ world, we see symbols and time because both arise from our body, the source of experience. So really, there is one world that contains both everything else and music.

Musical experience widens our world with this participatory knowledge—one that engages us at our deepest levels of being: our character2. The ways we come to make sense of the living experience of music are themselves how we make sense of our lives. How we perceive music is how we perceive our own being. And what we think and feel of our music reflects what we think and feel of ourselves.

🪻

Like all boundary-dissolving experiences, music plays with time, and we know this because time is gloriously warped and bent when we are immersed in our music. As shown before, meaning in music actually comes from the way time is changed by the sound. The profound moment in the concert when the woman realized, ‘This is the end,’ had everything to do with perceiving and understanding a moment in time as it relates, concretely connects, to the beginning.

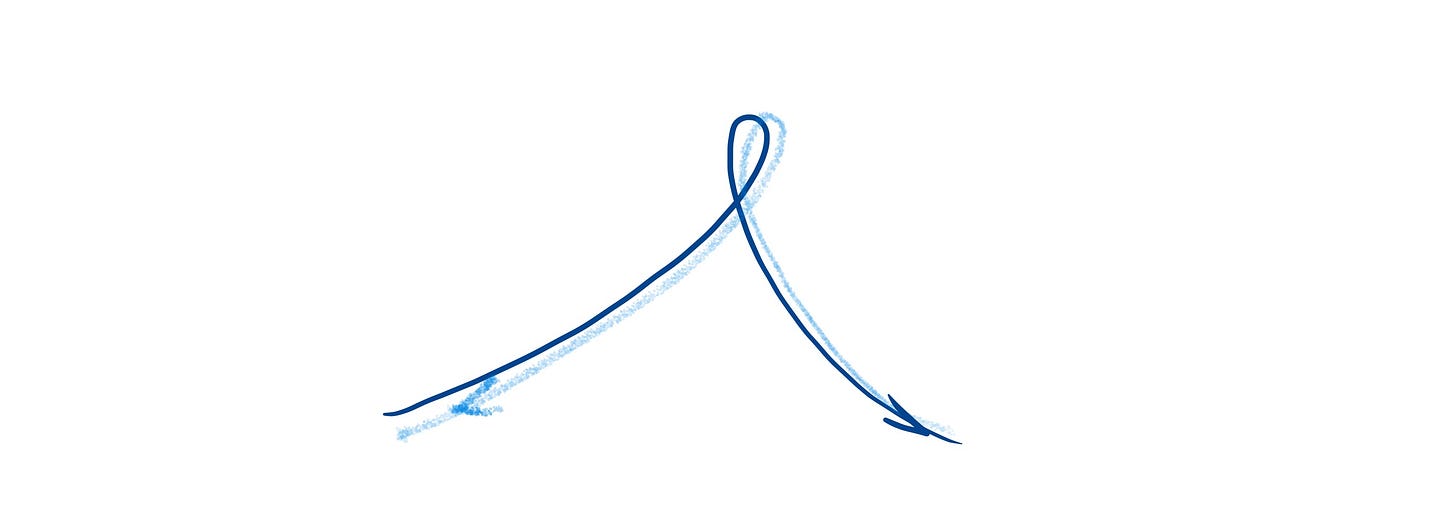

I drew the following diagram to illustrate how I hear time in narrative music without lyrics (i.e., classical instrumental music):

At any moment in the musical experience, there is a tension between the clock time of ‘this’ world and our internal sense of time, which behaves more like a vector that can change in both direction and magnitude. One time vector moves in the direction of the unfolding music, in the direction of ‘this’ larger universe. This is the more obvious direction of time, going clockwise, which moves from the past towards the future, towards our becoming. But that is not the only thing that we feel in music.

There is another time vector that runs simultaneously in the opposite direction, towards the past, flowing through our memory. It reaches all the way back to the beginning of the musical experience. Seen another way, this backward-moving time vector originates in our becoming and moves toward what has already been. It originates in the end, and appears to us through our present being. Backward-moving time pulls at us, pulls us out of the clock world and beyond it into the world of meaning.

The forward-moving time direction goes with the grain of chronological time. A central point I want to make is that forward-moving time is bodily and living. Not just chronological. Musicians/listeners are not merely playing/hearing notes “in time” like robots but are seeking wholeness while oriented toward the future. We try to hear the horizontal and the vertical, both the harmonic highs and lows and the arc from where we are at present to where we are headed.

Backward-moving time flows the other way and emerges like a non-verbal feeling. It is the more magical vector. There are those specific moments in a piece where the forward drive relaxes a bit, and our perception bends. We reflect, and through our act of reflection—which also emerges from our desire for wholeness while oriented toward the past—we generate the sense of duration: beginning-middle-end held together in one view. Backward time is the time of understanding. It speaks to us through a non-verbal understanding that comprehends the whole, saying: ah, this is a bar/melody/section/piece.

The two vectors, living and understanding, operate simultaneously and shift in balance over the course of the unfolding piece. The two create an evolving bidirectional ←→ force that grips at us in a way that’s unique to music. In the beginning of a piece, for example, forward anticipation is primary. But at the end, backward reflection takes over. And the climax is where these opposing forces are at their maximum, pulling at us equally (and can often tear us apart emotionally).

We can see now that the climax is not just an artistic event, but an existential one. Climax is not the name for the most intense part of the composition, the loudest or the most ecstatic. Climax is the moment in the piece where the overall temporal direction flips from future to past, from anticipation to meaning.

🌸

To close I’ll share a quote that inspired this, a principle of Søren Kierkegaard quoted from Gage Greer.

“Life can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards.”3

Kierkegaard understood this tension between past and future is what defines the human struggle for meaning. These realities are not just musical. They are human.

Through our reflection, we can see how, without any words, musical experience offers us an entire worldview. Let this silent worldview persist: the world is felt, whole, and interconnected.

Other related posts:

See The Master and His Emissary by Iain McGilChrist (Yale University Press)

See my post on the Four Ways of Knowing (on Substack)

See Søren Kierkegaard’s Most Profound Life Lesson by Gage Greer (on Substack)