Song For Athene speaks with the breath of reality—by being built through A:B contrasts and by flowing through cycles of building, climax, and resolving across time. It feels as though the composer, John Tavener, understood the shape of the patterns that underlie meaningful realities or experiences in story, perception, and sound itself.

Ever since hearing it I’ve always intuited that this piece is a living form of a pattern that creates meaning.1 It was a huge inspiration for me when I was a composition student. Built with proportion and vision, I looked at its form in my imagination, it being so easy to hold and turn with my inner eye, but I never wrote it down or took it apart in a more traditional way of musical analysis. This essay introduces some of what I’ve learned from opening the score and finding out some of its inner joy.

Before we dive in, a few general notes about the composition:

There are 7 big phrases. Each big phrase is composed of 2 smaller phrases: a call phrase and a response phrase. The call phrase is introduced by a solo tenor, and the response is typically sung by the whole choir. This pattern gets repeated with variations that build more or less tension through contrast and repetition.

As in Byzantine music, a continuous drone on F—an ison—underlies the whole work.

In some phrases, Tavener thinks in harmonic lines rather than chords. He goes beyond traditional major and minor harmonies and writes in modal counterpoint.

Dynamics play an important role in the structure of the piece. The written dynamic is as pianissimo as possible, throughout, until the 12th phrase, near the end, where everyone crescendos into forte for the first time, and where they remain, strong, singing the next phrase together as the voice of God: “Come, enjoy rewards and crowns I have prepared for you.”2

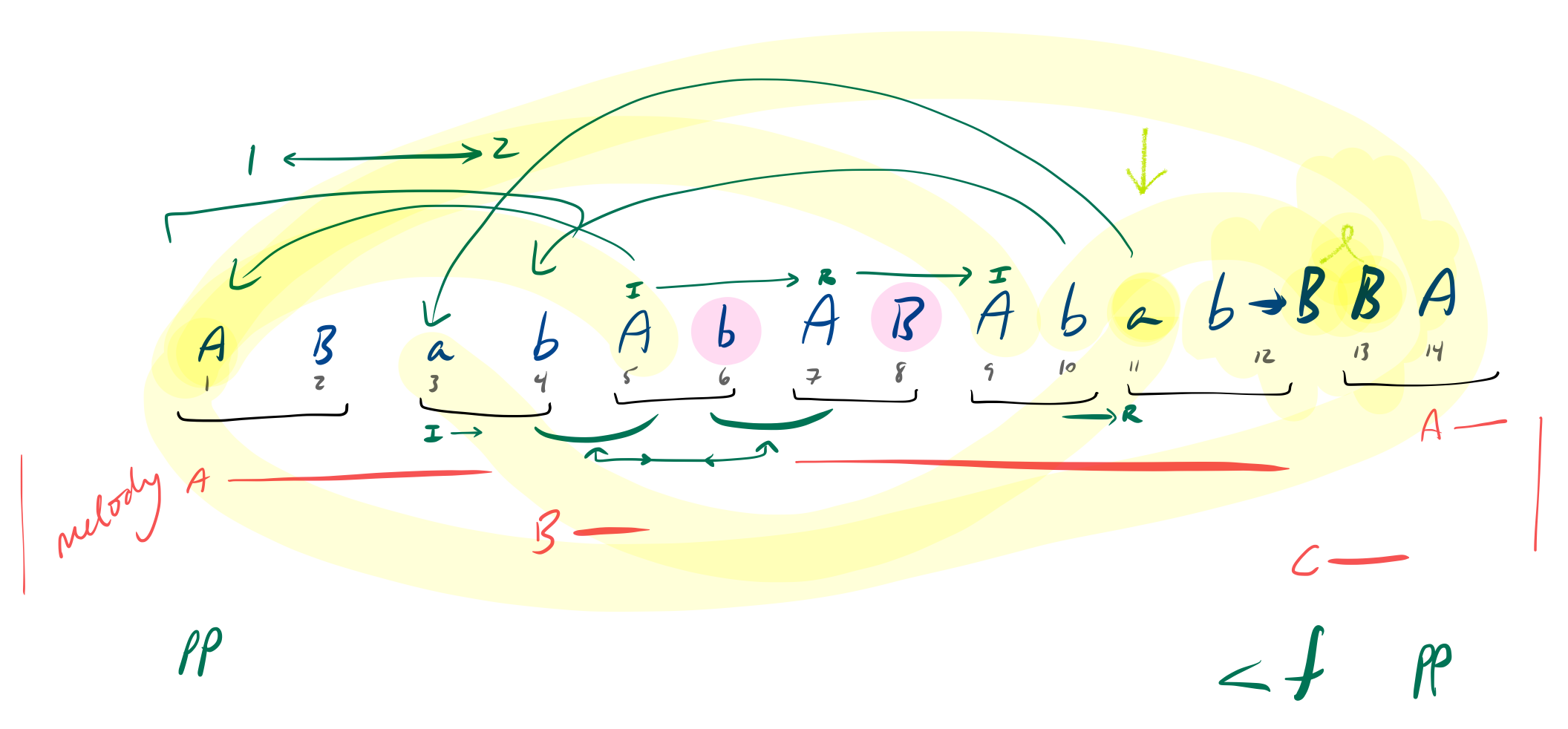

The piece orbits one central melody. Varied at key moments (phrases 4 and 13), the piece unfolds as one melodic shape repeated in different ways 14 (7x2) times.

Notice how the shape of the melody (fig. 1) is a reflection of the structure of the whole piece (fig. 2) and vice versa.

Tavener begins the Song with a contrast between the structure of this melody and the way it is sung. Structurally, the melody is two identical repetitions of the motif . A motif, or motive, is a melodic cell—the notes in the blue brackets. The red line indicates the phrasing as it is sung.

The tenor sings the end of the first word at the beginning of the second repetition. The intervals rise up at the end of the tenor’s breath, so he disappears for a brief moment at the start of the second repeated melodic cell, inhales, and then intones the rest of the motif. When he sings the second word, he’s already in the middle of the established pattern. For a western ear, the beginning of a pattern is often a metrically heavy place, but here, the weight of beginning anew is softened by the emptying of his lungs.

If he were a violinist and didn’t need to breathe, he could phrase the second half of this melody as a crescendo right through the repeated rising line, placing the metric downbeat—the one in the measure—on the first note of the pattern. But this of course would deflate the shape of the melody, and thus its meaning.

Here, and in all of his music, Tavener mirrors an interplay between a deep mathematical structure below and a soaring spirit above. Tavener sets us up with this tension at the start, and resolves it with the remainder of his composition. His steady use of repetition builds and/or diminishes our sense of where we are headed until, by the end, the melody becomes ours. Our expectation gets fulfilled.

This form diagram is a map of how the piece is heard, and how sections relate to one another through time. In the diagram, green arrows indicate the flow-direction of musical time. Notice the arrows between 1-2 and I-R? I and R stand for Impact and Resolution. 1 and 2 refer to a metric, our felt sense of where impacts and resolutions take place in space—or, in gravity: rise and fall.

I haven’t marked every instance, but these relations—1:2 and I:R—are the atoms of musical reality. They can be found everywhere. The richness is in taking the time to feel it first, and then label it second.

Form maps like this help you hear the piece at a distance. They help you understand the tonal-musical-poetic logic that lives in a composer’s imagination.

Here are some things I hear when I read this map:

Do you see the 7 call-and-response “sections” that underlie the 14 individual phrases?

The resonance between phrases 1 and 5 is clear, they are identical in sound. But we know, in experience, phrase 5 does not just repeat phrase 1. It opens up a tributary of backward-time3, flowing slowly at first, and gathering as the music continues.

Phrase 9 feels like the close of an even larger circle, arching back to phrase 1. The sopranos. Then phrase 10 arrives as a big second act, a second opening. “Life: a shadow and a dream,” sung softly in F minor, is a total moment of mourning. Entranced, we hear each following phrase grow in mass, the sopranos remaining in phrase 11 and growing beyond A and B into phrase 13: their crowning. Something that is at once both and neither.

And then, the circle closes one last time.

Lyrics by Mother Thekla

Alleluia, alleluia.

May flights of angels sing thee to thy rest.

Alleluia, alleluia.

Remember me O Lord, When you come into your Kingdom.

Alleluia, alleluia.

Give rest, O Lord, to your handmaid who has fallen asleep.

Alleluia, alleluia.

The Choir of Saints have found the well-spring of life and door of paradise.

Alleluia, alleluia.

Life: a shadow and a dream.

Alleluia, alleluia.

Weeping at the grave creates the song: Alleluia.

Come, enjoy rewards and crowns I have prepared for you.

Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia.

Tavener had come away from the funeral of Athene Hariades with the music of Song For Athene fully formed in his mind. He called Mother Thekla the same day, and said to her: "I want words." She sent him the lyrics by post, which arrived the next day.4

The lyrics alternate between “A” [Alleluia, alleluia] and “B” [Other lyrics]. The “AB” pattern reverses to “BA” on section 7 (phrases 13 and 14), with great significance, so the piece may end looking back at us on “A.”

A score study exercise:

Circle or highlight the moments in the phrase analysis above that contain the new quality of sound, something the ear hasn’t heard before. Notice how, in the experience, musical meaning is built up through novelty and repetition. For example, in line 2, the most salient new change is the shift in voicing from Tenor to SATB, full choir, still in a very soft dynamic. In line 3, the new change from before is in the harmony from Major to minor. These are moments of sonic surprise. The more you feel them, the more they have to say.

Song For Athene came like a flash from deep within Tavener’s mind. Built with cycles of call and response, the piece reveals itself as one great phrase unfolding over time. The piece is an act of meaning-making, spoken by a musical soul who saw, through sound, the deep patterns of the world alive with architecture and spirit. To see it is to hear it. Listen to Song For Athene on Spotify.

The final cadence

Tavener’s cadence here is one of those classic church cadences that crush you, like the motets and organ works of Bach, or in any of the Renaissance composers. This triadic cadence is propelled by a linear melody. The force of melody at this point of the piece carries us from its peak down through a (6-5-4)-3-2-1 cadence. Harmonically, a huge release; it’s all the F major scale. This cadence is a confirmation of the identity of the beginning melody, after it lived and doubted itself so many times over the course of its life, a resounding affirmation that it is exactly how it is.

Would you like me to create a companion post?

I’m thinking about analyzing the counterpoint and harmony on all 14 phrases in this piece, and include some commentary. Let me know if you’d like me to share in a future post!

Thanks for reading and feeling with me, friends.

For more, see my post on the 3:2 Shape of Articulation (on Substack).

See also: Revelation 2:10, 2 Timothy 4:8, Matthew 25:34, and John 14:2-3.

See my post on The shape of musical time (on Substack).

Quoted from Song For Athene (on Wikipedia).