Day Two: Discovering the Double

Harmonic Series Analysis

This post is part of 14 Days of Harmony, a free course for musicians who want to deepen their understanding of harmony, and learn how to develop their connection with sound as a result. You can view the entire course here.

When it comes to rediscovering music, sometimes it is beneficial to think outside of the box.

In our previous lesson we saw that deep inside every music note is a beautiful and increasingly complex order known as the harmonic series. This hidden order gives rise to a set of sound phenomena: a fundamental that vibrates at a given frequency, and its set of complementary and enriching overtones that vibrate at higher multiples of the fundamental. In practice, it's really only useful to work with the first 7-8 harmonics. Remarkably, the first 6 harmonics spell out a major triad, and you can hear it by singing just one note.

If there is anything that I may impress upon you before we move on to the musical intervals, it is this: that each time we write a note on paper, we are writing the fundamental tone that comes with its own set of harmonious overtones.

Why is it important for musicians to appreciate the harmonic series?

The first few answers to the question might seem obvious to those who have been performing music for a while, but when we are discussing fundamentals for the purpose of deepening our relationship with sound it's important to consider them.

1. You will improve your intonation. Not just knowing, but experiencing how the major third sounds in nature will result in better ensemble playing.

2. You will learn about the universal relations of the tones and improve your knowledge of harmony. The fact that the fifth appears so audibly above every sounding note gives this interval a much richer meaning when it appears in music. You can then work with or against that fact to create or resolve tension in a piece.

3. You develop the practice of deeply listening to the totality of sound, which will shape your entire approach to music making.

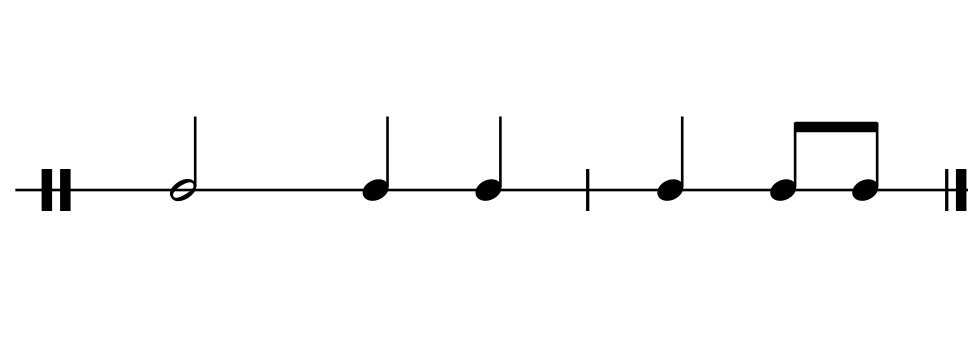

Let us now pose another question: how are figures 1 and 2 related?

Music: The Aesthetic Enigma

I mentioned briefly in my last post that music is different from any other art because it's the only one that has no model in our physical reality. The dancer, the painter, the sculptor, the architect, the designer—each artist adds meaning to the world by transforming its symbols and building upon them. It's easy to see how they each can find models for their art in our physical reality. But can we say the same about music? What physical model did Bruckner use when he constructed his symphonies?

Music doesn't have a model in the physical world, it simply refers to itself. Music is self-referent. We seem to derive meaning in music through repetition.1

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Letters from a Composer to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.